Jabir Ibn Hayyim

Abu Mūsā Jābir ibn Hayyān also known as Geber, was a prominent polymath: a chemist alchemist, astronomer and astrologer,engineer, geographer, philosopher, physicist, and pharmacist and physician. Born and educated in Tus, he later traveled to Kufa. He is sometimes referred to as the father of early chemistry.

As early as the 10th century, the identity and exact corpus of works of Jabir was in dispute in Islamic circles. His name was Latinized as "Geber" in the Christian West and in 13th-century Europe an anonymous writer, usually referred to as Pseudo-Geber, produced alchemical and metallurgical writings under the pen-name Geber.

His Life and Background:

His Life and Background:

Jabir was a natural philosopher who lived mostly in the 8th century; he was born in Tus, Khorasan, in Persia, well known as Iran then ruled by the Umayyad Caliphate. Jabir in the classical sources has been entitled differently as al-Azdi al-Barigi or al-Kufi or al-Tusi or al-Sufi. There is a difference of opinion as to whether he was a Persian from Khorasan who later went to Kufa or whether he was, as some have suggested, of Syrian origin and later lived in Persia and Iraq. His ethnic background is not clear,but most sources reference him as a Persian. In some sources, he is reported to have been the son of Hayyan al-Azdi, a pharmacist of the Arabian Azd tribe who emigrated from Yemen to Kufa (in present-day Iraq) during the Umayyad Caliphate.[ while Henry Corbin believes Geber seems to have been a client of the 'Azd tribe. Hayyan had supported the Abbasid revolt against the Umayyads, and was sent by them to the province of Khorasan (present day Afghanistan and Iran) to gather support for their cause. He was eventually caught by the Umayyads and executed. His family fled to Yemen, where Jabir grew up and studied the Quran, mathematics and other subjects. Jabir's father's profession may have contributed greatly to his interest in alchemy.

After the Abbasids took power, Jabir went back to Kufa. He began his career practicing medicine, under the patronage of a Vizir (from the noble Persian family Barmakids) of Caliph Harun al-Rashid. His connections to the Barmakid cost him dearly in the end. When that family fell from grace in 803, Jabir was placed under house arrest in Kufa, where he remained until his death.

It has been asserted that Jabir was a student of the sixth Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq and Harbi al-Himyari, however, other scholars have questioned this theory.

Theories

Jabir's alchemical investigations ostensibly revolved around the ultimate goal of takwin — the artificial creation of life. The Book of Stones includes several recipes for creating creatures such as scorpions, snakes, and even humans in a laboratory environment, which are subject to the control of their creator. What Jabir meant by these recipes is unknown.

|

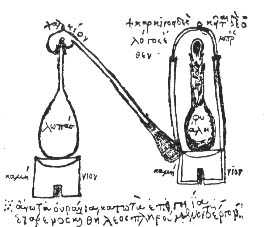

| Ambix, cucurbit and retort of Zosimus, fromMarcelin Berthelot, Collection of ancient greek alchemists (3 vol., Paris, 1887–1888). |

Jabir's alchemical investigations were theoretically grounded in an elaborate numerology related to Pythagorean and Neoplatonic systems. The nature and properties of elements was defined through numeric values assigned the Arabic consonants present in their name, a precursor to the character notation used today.

By Jabirs' time Aristotelian physics had become Neoplatonic. Each Aristotelian element was composed of these qualities: fire was both hot and dry, earth, cold and dry, water cold and moist, and air, hot and moist. This came from the elementary qualities which are theoretical in nature plus substance. In metals two of these qualities were interior and two were exterior. For example, lead was cold and dry and gold was hot and moist. Thus, Jabir theorized, by rearranging the qualities of one metal, a different metal would result. Like Zosimos, Jabir believed this would require a catalyst, an al-iksir, the elusive elixir that would make this transformation possible — which in European alchemy became known as the philosopher's stone.

According to Jabir's mercury-sulfur theory, metals differ from each in so far as they contain different proportions of the sulfur and mercury. These are not the elements that we know by those names, but certain principles to which those elements are the closest approximation in nature. Based on Aristotle's "exhalation" theory the dry and moist exhalations become sulfur and mercury (sometimes called "sophic" or "philosophic" mercury and sulfur). The sulfur-mercury theory is first recorded in a 7th-century work Secret of Creation credited (falsely) to Balinus (Apollonius of Tyana). This view becomes widespread. In the Book of Explanation Jabir says

Holmyard says that Jabir proves by experiment that these are not ordinary sulfur and mercury.

The seeds of the modern classification of elements into metals and non-metals could be seen in his chemical nomenclature. He proposed three categories:

- "Spirits" which vaporise on heating, like arsenic (realgar, orpiment), camphor, mercury, sulfur, sal ammoniac, and ammonium chloride.

- "Metals", like gold, silver, lead, tin, copper, iron, and khar-sini (Chinese iron)

- Non-malleable substances, that can be converted into powders, such as stones.

The origins of the idea of chemical equivalents might be traced back to Jabir, in whose time it was recognized that "a certain quantity of acid is necessary in order to neutralize a given amount of base." Jabir also made important contributions to medicine, astronomy/astrology, and other sciences. Only a few of his books have been edited and published, and fewer still are available in translation.